As more and more children potentially return to school, it’s safe to assume mask usage will be required in some if not most districts. We’ve seen in protests across the country that masks can be used as a form of self-expression. What limitations will schools impose on masks through health guidelines? And is it possible masks can unintentionally become status symbols? Unfortunately the framework for the latter already exists.

The closest analogue to mask guidelines is the student dress code. Sociologists David Crockett and Melanie Wallendorf (1998) have written about student dress codes as a method of controlling conflict, such as removing symbolism associated with gangs. However, they also talk about dress codes’ unintended consequences. “[C]ontemporary public school dress code uniform specifications typically focus on style and color but often do not specify any particular manufacturer, allowing market forces to compete for student purchases of uniforms” (Crockett and Wallendorf 1998:122). Though the intention of uniforms is to reduce disparities, Crockett and Wallendorf found that affluent students tended to wear upscale versions of a uniform, while lower-income students wore cheaper, mass-market versions. This makes uniforms, even though they are supposed to look the same, items of status and social position.

It might be a stretch to apply this to masks; however, students showing up with N95 masks will certainly stand out compared to students showing up in simple cloth masks. David B. Wooten (2006) conducted research on adolescents and clothing as stigma items. In one example, children interviewed for the study noted one student’s “limited wardrobe and the poor fit and finish of his trousers in their cruel jokes about his economic and social worth” (Wooten 2006:191). Wooten notes this type of ridicule conveys information about what constitutes as normal. This contributes to consumer socialization — the idea that certain brands have a higher social value than others. Basically, you’ll be cool if you wear X brand of jeans not the Y brand. Will that occur or has that occurred with masks?

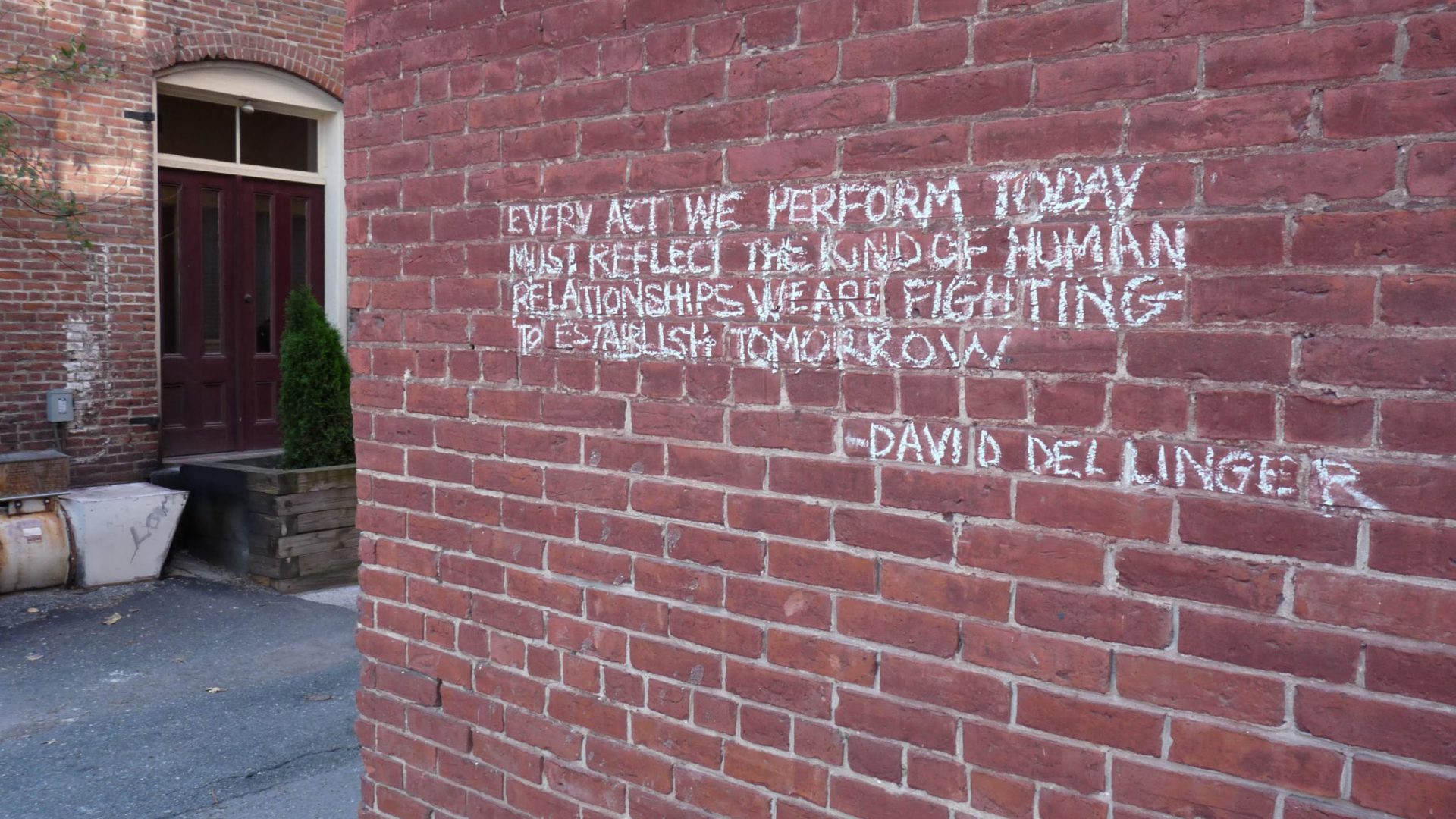

A more likely scenario when it comes to masks is student resistance. As Erving Goffman wrote, appearance is part of the “front” people put forward when communicating a social identity. On the other hand, dress codes are a method of social control by authority figures. Wearing a mask that states “Black Lives Matters” or “Health Care for All” may show others that the wearer identifies with certain beliefs, but is this protected speech in a school setting? Crockett and Wallendorf’s study found few instances of First Amendment-based opposition to school dress code policies. They note the case of a school district in Grapevine, Texas, prohibiting Doc Martin boots because of their affiliation with the Neo-Nazi movement. However, the school rescinded the policy after students protested the suspension of multiple students who were not affiliated with white supremacist organizations (Crockett and Wallendorf 1998:125).

Julie Underwood — professor of education law, policy, and practice at the University of Wisconsin-Madison — highlights court cases that back a district’s rights to restrict student speech (Underwood 2018):

- Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District, 393 U.S. 503 (1969): The speech is expected to disrupt the educational process or setting.

- Bethel School District v. Fraser, 478 U.S. 675 (1986): The speech is “plainly” lewd or vulgar.

- Morse v. Frederick, 551 U.S. 393 (2007): The speech promotes illegal activity, such as drug use.

The issue lies in the subjectivity of some of these guidelines. While speech that promotes illegal activity can be clear cut, “plainly” lewd or vulgar speech is harder to define. The same goes for speech expected to disrupt the educational process. These differ based on the values of the educators witnessing the speech. One educator might find “Black Lives Matter” to be disruptive while another might find it an important message and express solidarity. Underwood actually suggests that school uniforms are less legally fraught than dress codes because of their content and viewpoint neutrality.

Clearly more research is necessary. In terms of mask usage, research could be conducted in school districts that have been open during the pandemic, like in states such as Florida where the state government has resisted strict lockdown policies. This is a perfect topic for symbolic interactionists as well as conflict theorists. How would a public sociology approach this topic and help promote policies that avoid creating disparities while simultaneously allowing students the freedom of expression that is essential to public discourse?