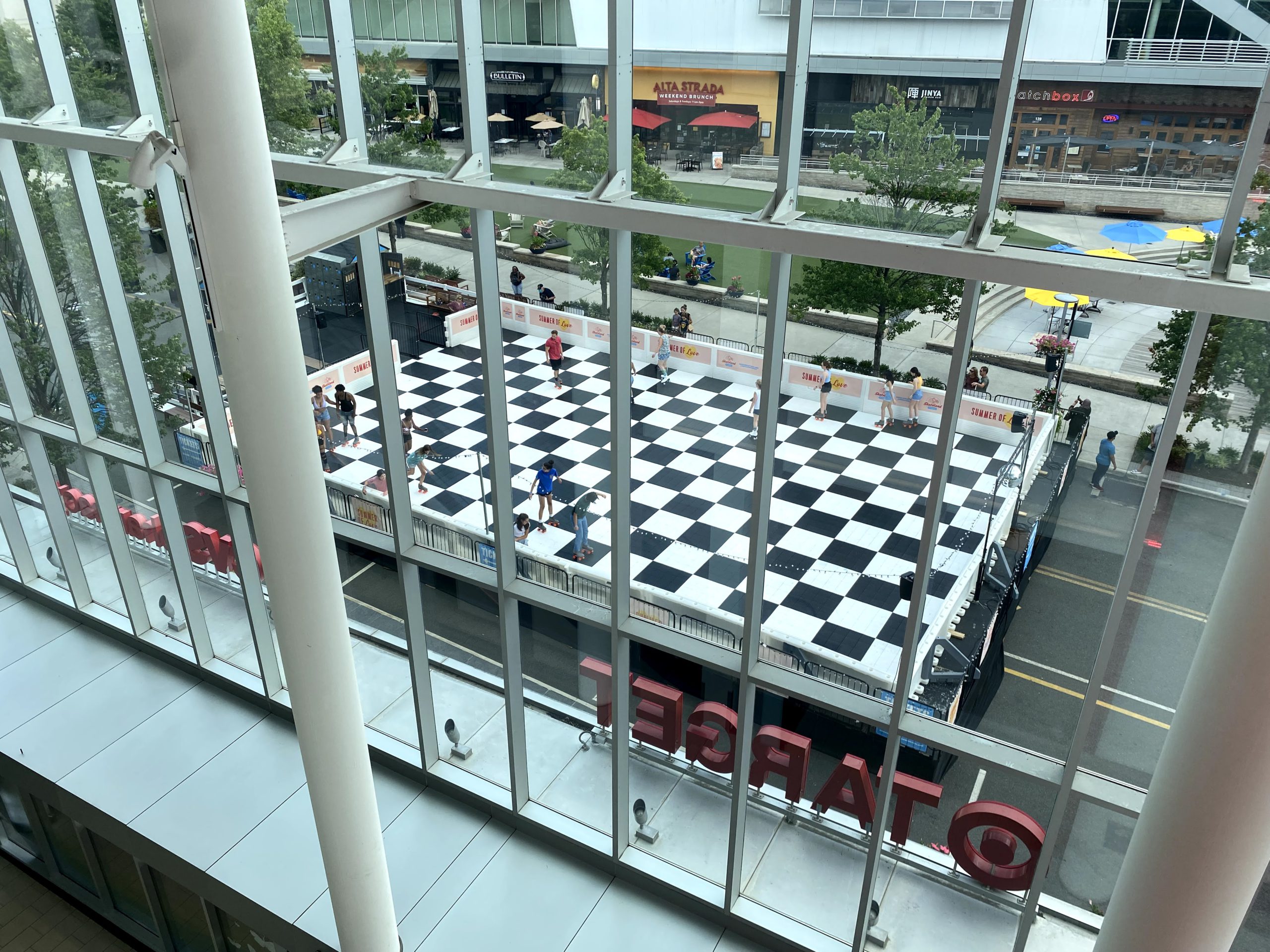

I am sitting on a bench in the Mosaic District in Merrifield, Virginia — an outdoor mall anchored by retailers like Target and Barnes and Noble. It is the type of shopping center that has become popular in the past decade around the suburbs of Washington, DC. While these malls tend to draw visitors based on retailers, they also feature outdoor activities, like ice skating rinks in the winter or giant chess boards and cornhole boards in the summer. This year, Mosaic has installed a large roller-skating rink.

My personal history with roller skating dates to the early to mid-90s, when I would go with friends to Skate Junction, an indoor rink in West Covina, California. Along with Raging Waters in San Dimas, it was the place to go to escape the hot San Gabriel Valley summers. It was dubbed a “local institution” by USA Today (Mohrman, 2019). But Skate Junction, like many other rinks, eventually closed.

It is neither fair nor accurate to say roller skating went away. James Turner and Michael Zaidman write in their historical account of roller skating (Turner & Zaidman, 1997, p. 92) that adults and “traditionalists” lost interest in the activity by the 1980s and it was seen by some as an activity for children. But adults have played a significant role in the recent history of roller skating — from the inline skate craze of the 80s and 90s to professional roller derby. And roller skating plays an important role in black culture, with rinks acting as a space for cultural diffusion through music and dance. It is probably more accurate to say that by the early aughts, roller skating had exited a “boom period” in the larger public consciousness.

But as COVID-19 took hold in 2020, something surprising happened: sales of roller skates surged (Kaplan, 2020). Because of lockdowns and general anxieties about gathering in indoor spaces, the activity, which was made for cruising sidewalks outdoors but without the steep learning curve of a skateboard, has regained popularity. That brings me to Mosaic.

It is abnormally cool and breezy for a day in July. Really, it is the perfect day for roller skating. There are about 30 people in the rink — a large rectangle with a chess board pattern that features the stereotypical disco ball on one end. Despite the disco ball, the music blaring from the speakers tends to originate from the 1980s — as if the people who selected the playlist thought the 70s and 80s were interchangeable when it comes to pop culture.

There is a mixture of families and groups of friends in the rink. A good portion of skaters hangout on the sides of the rink, which initially confounds me. It is $15 for an hour of skating. There are lockers for personal items because purses and backpacks are not allowed on the rink. But if you do not have a lock, the vendor will sell you one for $10. In other words, it is not a cheap activity. If you are spending $25 for one hour of skating, why would you choose to spend that time just hanging out on the side of the rink? I wonder if it is merely to be seen, as if participating in the activity alone grants the participant some sort of status. This is somewhat confirmed by the number of skaters who are pausing in the rink to take selfies or have friends take pictures of them.

To understand this type of behavior, researchers have used the “uses and gratification theory” (UGT) put forth by Blumler and Katz (Blumler & Katz, 1974) as a framework for analyzing social media use. UGT states that “people receive gratifications through the media, which satisfy their informational, social and leisure needs” (Phua et al., 2017, p. 115). For networks such as Twitter and Instagram, Phua et al. found that users were more likely to use the platforms in order to increase the number of weak ties that act as bridges to other groups (Phua et al., 2017, p. 119). Posting interesting content attracts attention, which in turn attracts followers, or weak ties. And weak ties have been found to be important to the process of disseminating information and resources, which leads to higher social capital and cohesion (Granovetter, 1973). Research on Facebook usage, in particular, has found a statistically significant correlation among women between higher self-esteem and perceived bridging social capital (Ellison et al., 2014, p. 862). In other words, we are addicted to likes because they build self-esteem and social capital. Activities such as roller skating are now seen as “interesting content.” And gender apparently contributes to this perception.

The ratio of women to men is highly skewed toward women. The only men I see on the rink seem to be either fathers helping a child or men in couples. The only men I see skating alone on the rink are older children, mostly tweens. I have a theory about this, and after observing two sessions and seeing the same results, I am confident it relates to masculinity and vulnerability. Roller skating is hard, and there is a good chance that if someone has never practiced, they may end up on their butt in front of strangers — both participants and observers. By agreeing to step into the rink, men are taking part in a self-disclosure of their weaknesses. But by helping a child or skating with a partner, they gain something from the experience. Helping a child is seen as being paternal and caring, thus increasing capital with a partner or potential partner. Skating with a partner is opening yourself up to vulnerability and showing yourself as willing to have fun, also a way of building capital. The man by himself does not have much to gain in terms of capital and a lot to potentially lose in terms of self-disclosure of vulnerabilities.

I decide that I am going to participate and skate, and I realize that with my status as a 41-year-old man not accompanied by friends or family, I am opening myself up to these vulnerabilities. But I am doing it for science. I buy a lock from Target for $3, because the $10 locks on sale at the rink are a scam. The rink will close temporarily at 1:15 p.m. for cleaning before the next session begins. I imagine a team of employees with cleaning supplies as COVID fears still exist thanks to news of increasingly infectious variants and outbreaks in unvaccinated populations. Instead, two employees, side by side in the type of plastic garden shed you could purchase at Home Depot, spray disinfectant in the shoes skaters rent. The employees wear masks, but they are pretty much the only people I see wearing them.

As I wait in line to pick up our newly disinfected shoes, there are a father and son behind me in line. The man looks to be about my age and his son is probably not much older than my own son — around 7 or 8 years old. The man talks about how he is worried whether the skates will be hard on his ankles. They had recently gone ice skating, and he experienced ankle pain afterward. I think back to my own experience as a kid with rollerblades and ice skates and how proper form really does play a role in avoiding ankle pain. That is less the case with roller skates, however, which are more stable thanks to four wheels, instead of a line of wheels or steel. But this makes me wonder again about masculinity and vulnerability. I am no stranger to aches and pains as I get older from what seem like the mildest activities. It could be that not only are men averse to displaying outward signs of vulnerability but also acknowledging limitations telegraphed by inward symptoms of vulnerability. Masculinity, at least the kind shaped by popular culture, tends to depict men, even as they get older, as perfect specimens and invulnerable to injury, like Tom Cruise in the Mission: Impossible franchise. If Tom Cruise can break his ankle pulling off an incredible stunt for a film and then turn around and continue filming, how dare we feel ankle pain?

As the session starts, the skaters shamble onto the rink like a horde of zombies, our bodies swaying awkwardly as the skates move in ways we do not intend to. I can even hear some groans as skaters attempt to hang on to each other to avoid falling. Even with my experience as a teenager, it is incredibly awkward for the first 10 minutes. I am already embarrassed.

The floor of the rink is not actually smooth but made of interlocking rubber mats, which makes me wonder if that is adding to the awkwardness. I am guessing, however, that the rink operators chose rubber mats for legal reasons. Already the kid who is accompanied by his dad has hit the floor several times.

As the session continues, my confidence and that of a few other skaters improve as we get the feel for the skates. There are a handful of us gliding across the rink effortlessly. The other skaters, however, cling to the side of the rink and either shuffle forward using the safety of the rink wall or talk with their friends. I realize my observation from earlier was missing crucial information: roller skating is not just hard, it is really hard. The participants still want to be seen doing the activity, taking pictures and videos to post on Instagram or TikTok as a way of increasing their social capital. But they are not using the activity to learn a new skill. I find this counterintuitive because I imagine being the teen in a group of inexperienced friends who is good at roller skating would increase your social capital. You might get some bumps and bruises in the process, but that is how practice works. It is becoming clear to me why I was not the popular kid in middle school or high school.

The speakers start blaring a song from 1983 called “White Horse.” It contains the lyrics (Stahl & Guldberg, 1983):

If you wanna be rich

You got to be a bitch

You got to be a bitch

I said, “Rich”

Rich

You bitch

If you wanna ride

Ride the white pony

I wonder if the rink operators are even monitoring the playlist or if they realize that “ride the white pony” is a euphemism for doing cocaine. It is a little surreal to watch families and groups of kids riding around the rink as the song plays. I am sure that the song would fit right in at the rinks of the 1970s and 1980s. I guess this is what happens when popular culture from another time is pulled into the present. All the meaning is transferred in the process, but it feels anachronistic rather than authentic. I also wonder how I would explain to my seven-year-old what a “bitch” is because we never use that type of language at home.

I call it quits after 30 minutes despite paying $15 for the one-hour session. The rink has also mostly cleared out, with only the skaters who are comfortable remaining. I have been skating in circles, and despite having fun, realize how empty the experience feels without people with which to share it. I think about getting a pair of roller skates just so I can roll around my neighborhood back home — a space more welcoming for solo activities than the public rink. Even then, my status as a middle-aged man makes me stand out, even within spaces where I can comfortably display vulnerabilities. Why are the activities of my youth socially deemed inappropriate for men my age? Toxic masculinity hurts everyone, including men.

References

Blumler, J. G., & Katz, E. (Eds.). (1974). The Uses of mass communications: Current perspectives on gratifications research. Sage Publications.

Ellison, N. B., Vitak, J., Gray, R., & Lampe, C. (2014). Cultivating Social Resources on Social Network Sites: Facebook Relationship Maintenance Behaviors and Their Role in Social Capital Processes. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 19(4), 855–870. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcc4.12078

Granovetter, M. S. (1973). The Strength of Weak Ties. American Journal of Sociology, 78(6), 1360–1380. https://doi.org/10.1086/225469

Kaplan, I. (2020, July 8). How to get around, get exercise, get cool this summer: Roller skating. Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/wellness/how-to-get-around-get-exercise-get-cool-this-summer-roller-skating/2020/07/07/971a2fde-bc79-11ea-bdaf-a129f921026f_story.html

Mohrman, E. (2019, March 4). Roller Skating Rinks Near West Covina, California. USA Today. https://traveltips.usatoday.com/roller-skating-rinks-near-west-covina-california-59899.html

Phua, J., Jin, S. V., & Kim, J. (Jay). (2017). Uses and gratifications of social networking sites for bridging and bonding social capital: A comparison of Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Snapchat. Computers in Human Behavior, 72, 115–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.02.041

Stahl, T., & Guldberg, J. (1983). White Horse [Recorded by Laid Back]. Medley Records.

Turner, J., & Zaidman, M. (1997). The history of roller skating. National Museum of Roller Skating.